“Colloidal gels,” ubiquitous in everyday products, divulge their secrets

Researchers at MIT have developed a new method for determining the structure and behavior of a class of widely used soft materials known as weak colloidal gels, which are found in everything from cosmetics to building materials. The study characterizes the gels over their entire evolution, as they change from mineral solutions to elastic gels and then glassy solids.

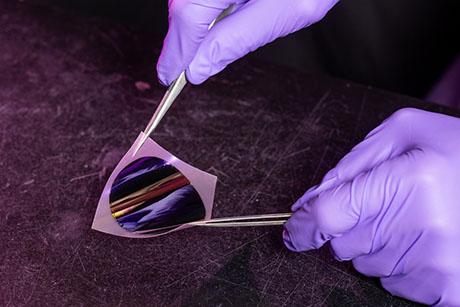

The work uncovers the microstructural mechanisms underlying how the gels change naturally over time, and how their elastic properties also change, both over time and depending on the rate at which they are experimentally deformed. This characterization should allow further study, prediction, and perhaps manipulation of the gels’ behavior, opening doors to advances in such areas as drug delivery and food production, in which these gels are common ingredients, as well as in applications ranging from water purification to nuclear waste disposal, which use these colloidal gels in a crystallized, porous form known as zeolites.

“We believe this new overall picture and understanding of the gelation and subsequent aging process is of great importance for material scientists who work on soft matter,” says Gareth McKinley, the School of Engineering Professor of Teaching Innovation and professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

“Our results enable researchers to determine why weak colloidal gels show aspects of both glassy and gel-like behavior, and to possibly engineer the gels to have particular desired features in their mechanical response,” says Bavand Keshavarz, a postdoc in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering and first author of the new study, which appears in PNAS.

The research was performed as part of an international collaboration involving MIT, Argonne National Laboratory, the French National Center for Scientific Research, and the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission.

Using aluminosilicate gels, widely utilized for making zeolites, the researchers overcame many of the challenges associated with characterizing these very soft materials, which continuously change over time, as well as exhibiting different properties depending on the rate at which that are deformed. Keshavarz likens their behavior to that of Silly Putty, which stretches and flows if you pull it slowly, but breaks off sharply if you give it a fast tug.

The gels also age quickly, which means that the mechanical behaviors they exhibit, while already varied at differing deformation rates, change quickly over time. Most previous studies focused on studying these materials in their mature state, Keshavarz says.

“They could not get an overall picture of the gel because the experimental window of their observations was rather narrow,” Keshavarz says.

For this study, the researchers realized they could put the gels’ aging process to their advantage through a framework known as “time-connectivity superposition.”

They subjected the alumino-silicates to a repeated series of complex deformation frequencies known as chirps during the gelation and subsequent aging processes. Chirps, modeled after the echolocation signal sequences produced by bats and dolphins, very quickly test the properties of changing soft materials.

By repeatedly applying the chirp signals throughout the evolution of the gels, the researchers developed a sequence of what could be thought of as informational snapshots representing the mechanical properties of the gels as they were subjected to a wide range of deformation frequencies spanning over eight orders of magnitude (for example, from 0.0001 hertz to 10,000 hertz).

“This means we have looked at the material behavior over a very wide range of probing frequencies,” says Keshavarz, “from very slow deformations to very fast ones.”

The resultant snapshots provided a comprehensive profile of the mechanical properties of the gels, allowing the researchers to conclude that weak colloidal gels, also known colloquially as pasty materials, have a dual nature, exhibiting features of both glasses and gels. Prior to this study, researchers’ limited observational perspectives led them to conclude that such materials were either gels or glasses, not having observed both features in a single experiment.

“One scientist says it’s a gel, and the other says it’s a glass. They’re both right,” says McKinley, comparing the gels’ characteristics to that of caramels, which exhibit the same principles of time-connectivity superposition as they are heated and can be either soft and chewy or brittle and glassy.

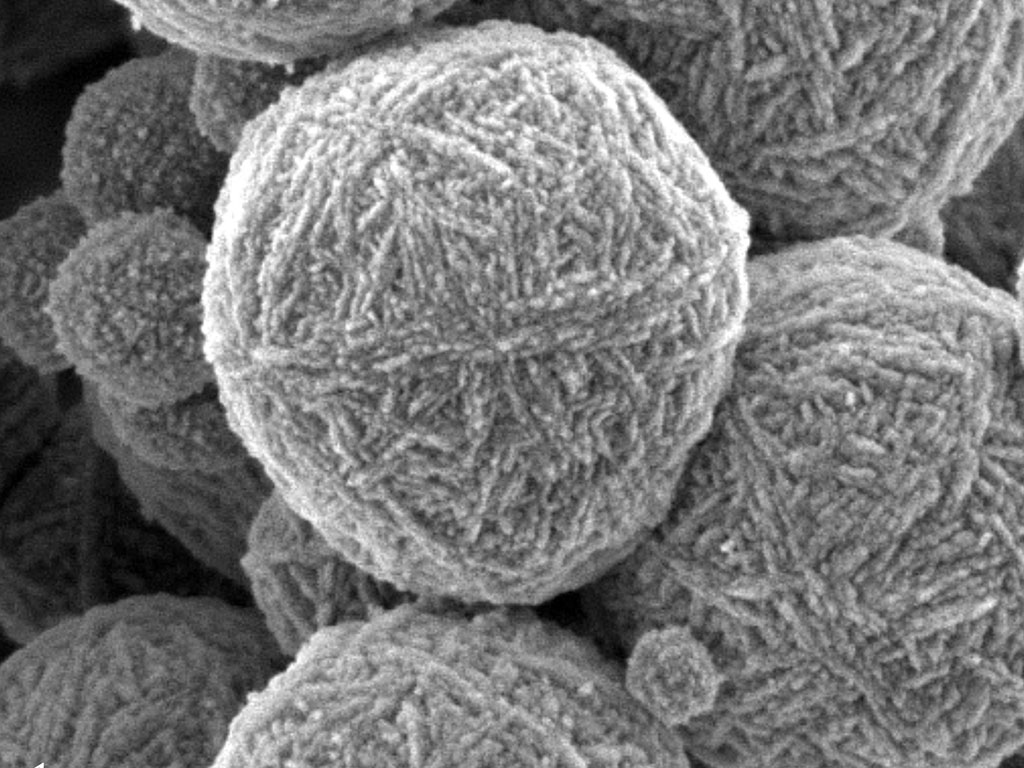

To observe the evolving structure of aluminosilicate gels, in addition to examining their mechanical properties throughout the gelation and aging process, the researchers applied X-ray scattering. This allowed them to resolve the structure of the gel starting from when its chemical components were smaller than the wavelength of light and therefore invisible without the penetration of X-rays. The process allowed the researchers to observe the physical structure of the gels at length scales ranging over four orders of magnitude, zooming in from a scale of 1 micron down to that of 0.1 nanometer.

Observing the gels at such wide-ranging spatial scales, the researchers discovered that the fractal-like network of connected particles that develops as the particles cluster into a gel remains fixed beyond the gel point. The network grows and adds clusters, changing in scale, but the main structure or “backbone” and geometry remain the same.

Examining the materials over such widely-ranging spatial scales and combining this information with the concurrent information about the materials’ mechanical behavior, the researchers also concluded that larger clusters within the network relaxed more slowly in a gel-like manner after being deformed while the smaller clusters relaxed more quickly like a rigid glassy material. McKinley makes the analogy to the marked differences we experience between the time it takes for a memory foam mattress to recover from being compressed versus the time a very hard conventional mattress takes. Observing this relationship between the size of clusters within the material and the rate of relaxation sheds further light on the origins of these soft materials’ distinctive properties.

“Our work opens up a novel perspective,” says Keshavarz, “and paves the path for researchers to develop a more comprehensive view about the nature of these pasty materials.”

“Colloidal gels are ubiquitous materials,” says Emanuela Del Gado, associate professor in Georgetown University’s Department of Physics, who was not involved in this research but has collaborated with the MIT team in the past. “Their physics is important in so many industries and technologies (from food to paint, to cement, personal care products and biomedical applications). This paper is the first attempt to identify the microscopic traits that unify the mechanics of a potentially wide class of systems, by connecting [the gels’] microstructure to their rheological behavior.”