Peer coaching helps graduate students thrive

Eventually she became aware that her PhD was taking longer than average, which fueled her doubts. When the pandemic delayed her research, she worried about falling even further behind.

Then, in the spring of 2020, she got an email about the launch of the Mechanical Engineering Graduate Coaching Program for students. Her first reaction was, “What do I have to lose?”

Over the ensuing coaching sessions, which took place with small groups of peers each week, Wang discovered that many other students were also grappling with doubt and anxiety. She learned to reflect on what she really wanted out of her MIT experience, break her goals into small steps, and accept more support.

“I was not very cognizant or aware of the type of environment I needed to thrive,” Wang says. “The analogy I like to use is we don’t think of a fish as a bad animal because it can’t live on land. It thrives in water. So, it was about finding the environment I needed, and until then I didn’t understand the importance of environment.”

Since those early sessions, the Graduate Coaching Program has helped hundreds of students through group coaching sessions, accountability groups, and summer workshops. It has also expanded to offer its services to graduate students from other departments, with some events open to every graduate student at MIT.

“We’re creating a community through this approach of supporting each other in what we call the coaching mindset,” explains program creator Kelli Hendrickson PhD ’05, who also works as a research engineer at MIT.

Hendrickson draws a distinction between coaching and mentoring or advising. In her view, coaching creates a unique partnership between peer coaches and coachees to find creative solutions that foster personal and professional growth. One way she describes it to mechanical engineers is to think about coaching as collaborative product development, with the student as the product.

“Sometimes there’s a little bit of a lottery you win as a graduate student in terms of getting enough support from people in your immediate bubble,” Hendrickson says. “What the coaching program is trying to do is provide a new way to support students outside of their principal investigators and other people you may normally think of.”

Hendrickson had been thinking about starting a coaching program for years when the pandemic hit. As a former graduate student herself, she saw the unique challenges students struggled with firsthand.

“With everything going virtual, there was definitely a big need,” she recalls. “Coaching seemed like the missing piece in students’ support.

Early sessions made it clear students could benefit from coaching even beyond the pandemic, and the program has continued to grow. Today, cohorts of three to seven graduate students meet in confidential sessions each week to go over coaching skills as well as topics related to their personal and professional goals.

Meetings may have themes around common challenges like prioritization, goal setting, and stress management. Students also often seek help for making transitions in their careers, whether it be switching thesis topics, moving research labs, or beginning their work careers.

“The students really build trust and start to get to know each other through the weekly sessions,” explains Wang, who currently works as a postdoctoral research associate at MIT and is an instructor with the coaching program. “They’ll start the semester learning coaching skills, and they get to practice over facilitated discussions. Then they transition to group peer coaching, where one person brings in a topic that is pertinent to what they’re going through, and then the group acts as the coach to help them explore that topic and ask questions.”

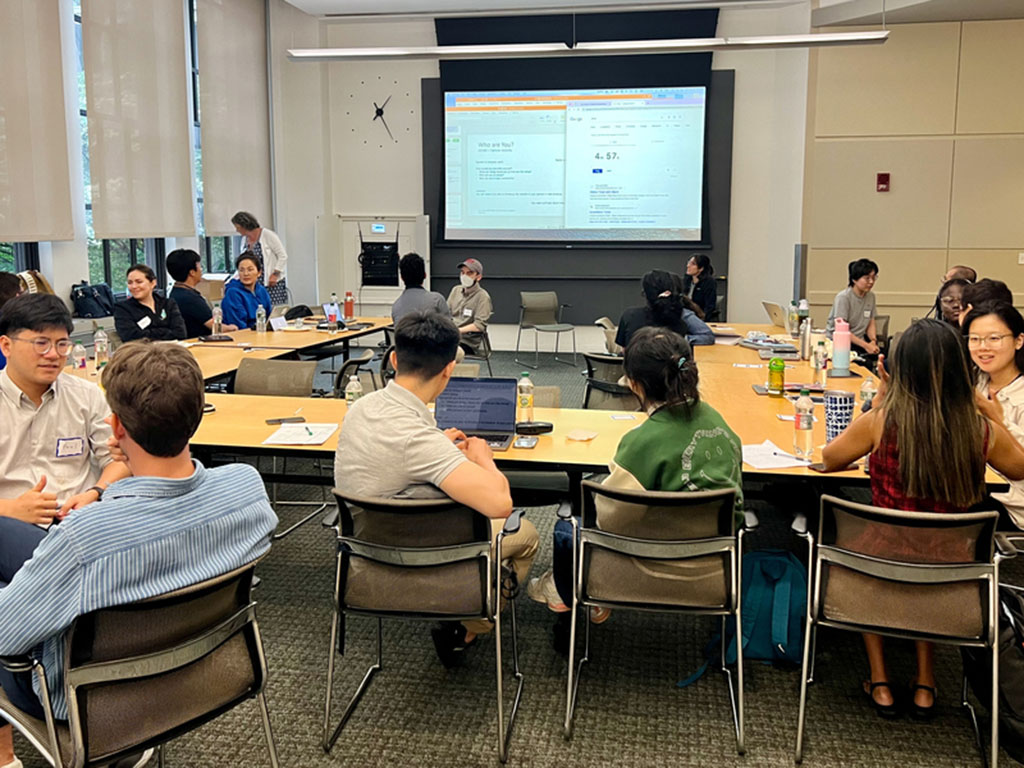

The coaching program also organizes accountability groups for students to discuss their work, reflect, and set new goals in a nonjudgmental and supportive environment. This summer, it hosted a three-day workshop open to all graduate students through support from the Riccio Graduate Engineering Leadership Program (GradEL). The workshop was so well-received that the program’s organizers decided to hold it again in the upcoming Independent Activities Period.

Students report that the approach has helped them become more effective researchers, mentors, collaborators, and labmates to their peers. Some issues students commonly get help with are burnout, imposter syndrome, and dealing with internal pressure or negativity.

“It’s very common at the end of the first session for students to say, ‘I’m so glad I’m not the only one struggling with these things,’” Wang says.

“We spend a lot of time on that word, ‘should,’” Hendrickson adds. “Students say ‘I should be able to do all of these activities, participate in all these groups, do my research, and take this high course load. Somehow not doing all those things is a failure. Perfectionism is something we see a lot.”

Last spring, through a partnership with MIT’s MindHandHeart initiative and a grant from the Chancellor’s Innovation Fund, the coaching program began a workshop series open to all graduate students around topics including defining success and career exploration. The events helped the organizers learn about other departments where MIT graduate students could benefit from their work. They recently opened up the weekly coaching sessions to students in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and hope to continue expanding.

“This couldn’t have been possible if students hadn’t come in and trusted us, and if leadership hadn’t bought in,” Hendrickson says. “That was really important.”

With every session, the program not only helps students with their own problems but also equips them with skills to help their peers and make MIT a more supportive place.

“A key thing we hear from people is we help build a sense of community,” Hendrickson says. “Especially if your lab group is small, your living arrangements are small, and also you stop taking classes as you progress in your PhD work. It can feel like you’re on your own for a long time. Trying to find a sense of community that still feels like it’s helping you develop and move forward is a big reason students join the group.”